[As published in Hindustan Times, Mumbai, and Times of India, Goa, on 13th December 2011]

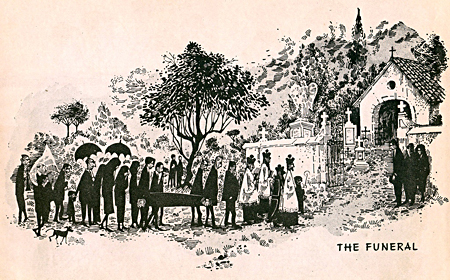

It was the 1970s. Goa had started to lose itself. Not to foreigners, not to Indian immigrants or land sharks, not even yet to corrupt politicians – but to ourselves. We had started looking upon all old things Goan with impatience, and couldn’t wait to bring in the new. Beautiful colonial homes and churches were given a modern concrete facelift, old pottery and utensils were allowed to disintegrate, Konkani tiatr [theatre] troupes shied away from sophisticated city folk… and in the middle of all that Goa negligence, came Mario’s iconic book ‘Goa with Love’.

It showed us, through uncanny detail and irreverent wit, that we were in fact very nostalgic for the things we had lost and were in the process of losing. The old carreira, the village baker and the vicar on their bicycles, the good cheer in the village taverna, the buxom but hot tempered fisherwoman in a crowded bus…

Mario had been publishing cartoons of national interest in leading Indian publications for years. But in Goa, national fame counted for little; he remained practically unknown in this Asterix’s village, where nothing exists unless it is fully Goa-centric. ‘Goa with Love’ established him, in one stroke, as one of the soil’s favourite sons. He became ‘our’ Mario, the brother who showed us who we were.

Mario and I shared a private joke. Every time we met at a party, which was very often, he would greet me with “So when are you going to pick up your guitar and sing for us all?”, and I would retort “As soon as you pick up your sketch book and sketch us all.” It wasn’t funny to anyone except the two of us, and that too simply because we repeated it predictably for years on end.

In the early 80s, his then adolescent sons Maushi and Bodkis wanted to pierce their ears. A very worried Mario took me aside and said “Please talk them out of it. They’re trying to imitate you. I told them they have to be successful and famous before they can do this sort of nonsense.” I said “Mario, I can’t believe this! You’re an artist; how can you of all people be against your sons wearing ear-rings? You could wear a couple yourself!”. I think what I said sunk in somewhere, because ear-rings they wore, though Mario didn’t. For all the whacky cartoons he gave us, Mario was extremely classic. In looks, in taste, in comportment, and I daresay even in thinking.

I first met Mario when I was invited to a party in his apartment at Oyster in Colaba. I was a young architecture student in Mumbai who was meeting his first celebrity hero. That he happened to be a fellow-Goan was just an added bonus. That day he told me “I envy you musicians.” I couldn’t believe my ears. He explained “Look what happened just now. You sang a song, and received instant applause and appreciation from the people around you. I create my cartoons late at night, alone in my study, with no one to share the thrill with. By the time they are published and people compliment me, days or weeks later, to me they are stale and all but forgotten.” His words echoed in my mind years hence when, besides performing on stage, I also started the lonely journey of recording my songs all alone in my studio late into the night.

To me, Mario’s passing is not a loss. Many people go in their 80s. Both my parents did. Mario lived a very full and fulfilling life, and he died at home, in his bed, in his sleep, without major ailments, with the love of his life by his side. Two days earlier I met him at Nostalgia, a gourmet Goan restaurant, where he shared a hearty meal with wife Habiba, a glass of red wine in his hand.

No, the word loss somehow does not come to mind at all. I rather prefer to contemplate upon what an immeasurable gain Mario’s life was. To Goa, to India, to the world; and to me, one of the many people who are privileged enough to consider themselves his friends.